‘Americans Them’

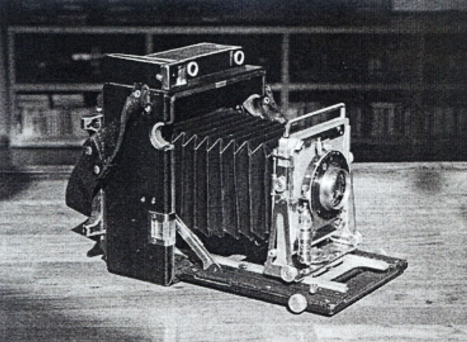

+Speedgraphic Graflex Camera

In 1989, in a small camera shop in Columbus, Ohio, I found a used Graflex camera which seemed to be carrying a story of its own. The camera body was covered with so many scars that it made me wonder if its former owner might have been an active journalist in the 1930s. I wondered whether I could really take pictures with that camera. Although I was apprehensive about the camera’s capacity, I tested it the next day, and in spite of my original doubts, the Optar lens of f4.7 yielded surprisingly clear pictures. It was then that my thoughts immediately began to be congealed with raw images of Weegee. After tightening up a few loose screws and oiling every bit of the camera, I set out to take pictures in the streets. As it turned out, it took me a year to get used to the camera’s rangefinder; it being as small as a keyhole.

+Festivals, Auctions and Parades…

Festivals, Auctions and Parades… Every weekend, one of these events occurs in the American countryside. Apple pies, hotdogs, soda, lemonade… By the time Randy Travis’s or Willie Nelson’s jolly country voices flows from the loudspeakers, people with a couple of silly jokes to toss around begin to gather on the street with beach chairs and ice boxes. When a parade car with a huge Burger King logo appears along with a nearby school brass band, people are willing to give away unsparingly, exclamations like “Wow”, “Oh, My”, or “Fantastic”. Parades always end with a solemn appearance by the old veterans with Stars and Stripes. “Are you Chinese?” “No, I am Korean.” “What kind of camera is this? It’s so big!” “…Can I take a picture of you?” “Who? Me! Why?” After a few words, I thrust my camera in front of the subject to whom I approached somewhat awkwardly. He then looked at me with a curious face wondering why this little Oriental man was trying to photograph him with a big used camera. I myself, however, really didn’t know the answers to his questions. For it was at this period that I think I was pretty much occupied by the faces I used to see in Diane Arbus’s or Weegee’s photographs, or David Lynch’s or Martin Scorsese’s films. Even after the developed negatives filled a complete file, I still couldn’t figure out what I wanted.

‘I See a Tenuous Distortion on Their Faces.’

Distortion… I was about a year into this project when this word vaguely hit

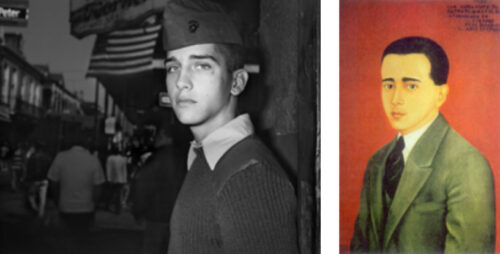

me. Perhaps this word might be an unconscious incarnation of my reaction to the stares I received from the American people. The Korean people I had met before coming to the US carried a rather apparent inflection in their distant gazes. They were obvious signs of a pain in life. A pain which usually comes from poverty or a disobedient child. But sometimes, in the gazes of the American people, I see some inflections that can’t be clearly defined. For example, I still can’t forget the gaze of this one boy I encountered in New Orleans. His eyes were shaded with a kind of ungraspable sorrow which could not merely be dubbed as general sadness. While confronting his gaze, I strangely came to think about his father. Quite curiously, I came to think that his father might have been the cause for the sadness in the boys eyes. In that short moment of me taking a picture of him, a lot of different things flashed through my mind. As far as I remember, the boy did not even breath a whisper to me. Two years after taking that picture, a gay painter I knew remarkably got interested in it, and so I exchanged it with a painting of his entitled, “TV Party”. The painting, an abstract one, was about a weeping mother and a father. I had to visit his studio to carry it out since it was quite big. I then got startled while looking at a Frida Kahlo’s

book that the artist handed me. For in her book, I found a portrait that so resembled the boy. I still don’t know why I felt his father from the boy’s eyes but I still believe that his father must have had some influences on the boys sadness.

“Past landscape emerges and forms one, two islands.” (Choi Young-mi, poet)

I have always thought that each human face carries a very specific and unique story. Whenever I take a photograph, as if looking at a navigational chart, I try to find small islands hidden in the landscape of the face. Sometimes my imagination is very vague as in the case of the New Orleans boy, but in most cases, a persons chronicles appears so sharply in their gazes and faces. In the Cohen brothers’ film, Fargo, very dry faces appear; faces with neither any story nor preconception . . . Most of their faces can be caricatured in a few simple lines. From portrait to abstract . . .

In Walker Evans’s American Photographs, I often encountered figures with such empty gazes. Just as an old church remains the same old church regardless of whether it is a Presbyterian or a Baptist. What matters to me is that such empty faces symbolize the ambiguousness of American culture. Like a map with a white space and a few simple letters like ‘Atlantic Ocean’ on it, their appearance from which the past landscape has been excavated makes me experience an undiscernible identity of American culture.

+Facade

“You look quite confident.” “Don’t let my confidence fool you! It’s only a facade.” A man I met at the Kentucky Derby talked about a somewhat unfamiliar word ‘facade’. This word, which can be interpreted either as outside or frontal appearance, plunged me into serious thoughts about portraits. Does a good portrait necessarily have to convey the interior of the subject? In fact, I think I see only what I can be seen in a photograph. This is why I feel burdened by an seasoned photographers’ advice to consider the inside of the subject since I believe, for some people, their facades could be their inside. In Arbus’s photographs, the facade is so raw that I become so perplexed when looking at them. Sometimes I feel my perception being blocked by all those raw facades to a point that prevents my perception from advancing beyond the point of just seeing. Like a drain through which water pours out fervently, her photographs have a very strong power of absorption. However, what remains after all is a fully emptied drain like a black hole. In this case, wouldn’t the facade be the essence of the subject? In discussing Arbus’s photographs, a flash also plays a great part of my works in articulating such a facade. As she said when using a flash, photographers don’t see what they are photographing until the moment they take pictures. However, as in a mug shot taken of a criminal at a police station, the details and textures created by the flashlight inscribe all the traces of the incident gone unnoticed on the spot. Thus, the flashlight keenly keeps one’s imagination geared towards the invisible from proceeding further. After finishing the project, American Them, I returned to Korea and embarked on producing portraits of now-forgotten old actors and actresses. A lot of people talked about the vanity, joy and sorrow of life in the entertainment world, but such things were based on nothing more than their reactions. Actually, those composures were just another facade.

+American Them

Once in the past I met a Japanese collector of Walker Evans’ photographs. In quite a solemn manner he unveiled an original print from a leather case that looked as old as Evans’s pictures. As I expected, the photograph was of an old church. I remember that the photograph felt quite heavy as the weight of its time. As if impatient to wait any longer, the collector began a lengthy and serious explanation about the value and the background of this original print. The only thing left in my memory of our conversation, however, is the simple facade of the church which creates ambiguity because of its obviousness. But the church is just a church and the photograph is just a photograph. Last summer, I had deja-vu with so many churches I saw, and Evans photographed while travelling in the Eastern part of the United States. In 1990, I once went past a place similar to a place which I knew of in the Ohio countryside, same old freeway, McDonalds restaurants, a shabby gas station with rotten pumps . . . Won’t there be the same festivals, auctions and parades that I used to see in the Ohio countryside? Perhaps after ten years there will still be the same festival beginning with a parade car with a big Burger King logo and a nearby local school brass band and ending with the solemn salute of old veterans from the American Legion. There might still be a Chinese or a Japanese photographer like me, who gets perplexed with confronting the empty faces of Fargo while looking for ‘raw’ figures of Arbus or Weegee. Regardless of whether they use a scarred Graflex or a brilliant digital camera, won’t they be confused about the curious identity of American culture if they see Walker Evans’s old church standing in a surreal mood in the same place? Then they will experience Americans as ‘them’, as perpetual others.

April 3, 1997, after finishing American Them…

© 1989-2024 HEINKUHN OH