Interview with Hein-kuhn Oh

Sunjung Kim

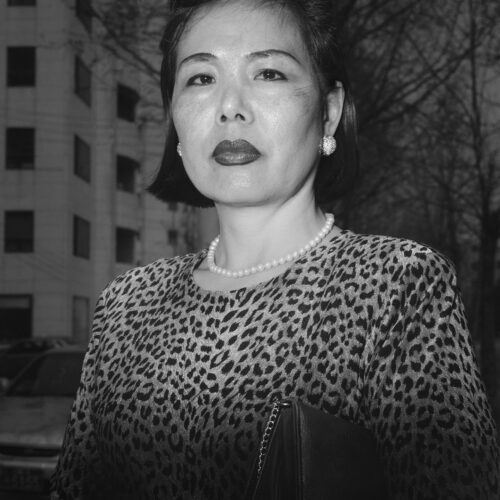

I began to take interest in Hein-kuhn Oh when we were working on a group photo exhibit in 1993. Hein-kuhn Oh and I have teamed up as artist and curator starting from that time, followed by the group exhibit of Saeck in 1995, and the Ajumma Exhibit that opened one year after the establishment of the ArtSeonje Center in 1998. This interview took place in 2012 during the preparation time for his solo exhibit at the ArtSonje Center.

Middlemen

SUNJUNG KIM: The soldiers project seems to be a different approach from your previous work. In your earlier work there was a lot of documentary, but starting with the Ajumma project onward you focused more on pure portraiture. The Girl’s Act and Cosmetic Girls projects, as well as Ajumma dealt with women of different age groups from a sociological perspective.

HEIN-KUHN OH: It was in 1991 that I began a full-time career as an artist and worked on Americans Them, Itaewon Story, and Gwangju Story until 1996. Until then, I viewed myself as a documentary photographer. But then the Ajumma project, which I started in 1997, is when I turned from being a documentary portrait photographer to a portrait artist. This doesn’t mean that I completely discarded the nature of documentary photography in my new work; instead if my previous work showed events and provided a narrative, then starting with the Ajumma project my work centered exclusively on portraiture. It occurred to me that ultimately, I could tell a documentary story in a minimalist manner through portraiture. At any rate, around that time was the turning point for my work and after that it led to a decade of portraiture work such as Ajumma, Girl’s Act, and Cosmetic Girls. And I just inadvertently happened to pick all women as my subjects, but it wasn’t like I had planned to work on the women trilogy project from the beginning. In-between, I worked on the “Ajussi” project, as well as “Pretty Guys,” but just did not end up exhibiting them. I wanted to disclose the prejudice and the bigoted attitude of Korean society through portrayal of Korean women with their insecure identities.

The current project has to do with soldiers – when and how did you get started?

I had been working on a minimalist documentary approach to an “individual portrait” for the past ten years, then one day I kind of became fed up with it. I thought, either I should start something completely new, or go back to the basics of documentary. At around that time, there were many political events which brought out crowds, and I began to question the notion of the egocentric and exclusionary “we” that Korean society adheres to; consequently, I got interested in “group portraiture” in which you can see dozens of people, considered as “us.” But it’s impossible to photograph all the existing “us” groups in Korean society and it made me wonder which one represents the most symbolic concentration of “us” in Korea. And “the military,” of all entities, came to my mind. The other portraits of groups that I had hitherto photographed were all those who belonged to a set of people who displayed social prejudices and common ambitions, but the military in that sense is far from such. Not only that, it is an institution that is based not on personal desire but duty; therefore I had to take the utmost caution in dealing with it. Nonetheless, I felt the military was the origin of the “us” nature of the Korean society, and since I had repeatedly photographed women until then, I decided to tackle the military, which consisted of men only. I then took various measures to contact the military, and also asked a friend in the army, but could not obtain permission for the shoot. As you know, the military is the most exclusive organization that is averse to any exposure. For about almost a year, I tried my best but finally gave up. Then suddenly, in 2009, I received a proposal from the Ministry of Defense to photograph them in commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Korean War. Ten photographers with diverse expertise, including me, participated in the project that had to do with photographing landscape, still life, and documentary, etc. I was assigned to do the portraiture. At any event, I gladly accepted the proposal, and worked on the project for three months. The Ministry of Defense gave its full support, such as providing a bus, cooperating with me in terms of location, selecting the subjects, and all that. After I had officially completed the assignment, I made a request for a one-year extension and fortunately they granted it, which made it possible for me to finish the current project. What’s interesting is the concept of the “us,” that was initially there in the portraiture of this group disappeared; and that’s because the soldiers did not feel like “us” but became “them” to me in the course of working on this project.

You said the soldiers project came about with your interest in the concept of “us.” But as I see it, Girl’s Act, where you inserted the girls in a circular frame, was an attempt to trying to get at the notion of “us.” What do you see as the difference between the Girl’s Act and the Middlemen?(Page 139, Girl’s Act)

The Girl’s Act project was not an “us” that I was part of, but an “us” that I was looking at because it was not a group that came about autonomously but, instead, was one that I constructed. In some ways, of all the groups of portraiture I worked on, there was not one that I viewed as “us.” For example, Cosmetic Girls was also “them” for me, and not an “us” that I had constructed. I was never once an insider sharing the context of their lives.

Is it because you are a male artist that you don’t have an “us” view of Girl’s Act or Cosmetic Girls? Is that why you looked at them from an outsider’s point of view, so to speak?

When I was working on Portraying Anxiety last year, this is the first thing I wrote in my notebook, “I am intrinsically comfortable looking at other people’s anxiety.” I have never photographed as an insider, like Nan Goldin; in effect, it’s easier for me to have an outsider’s perspective, like Diane Arbus. The middle-aged women or the girls wearing makeup, they are all “them” to me. Likewise for the Middlemen project, I took strictly an outsider’s viewpoint in photographing the soldiers. Come to think of it, during my first project, the title for Americans Them arose because I viewed them from an outsider’s point of view. Looking back, Ajumma, Itaewon, and Gwangju projects were the same. My work up to this point for Middlemen, also indicates that I don’t regard them as “us,” but “those soldiers.”

Is there any connection to your calling the soldier series, the Middlemen to Bourdieu’s Photography: A Middle-Brow Art?

Photography appeals to me because it is not a perfect art or medium. If one has to assess the position of photography I would characterize it as in-between art and media. It is the incompleteness of it – the “middleness” of it that always fascinated me. Bourdieu has no bearing on my current soldier portraiture but since the Ajumma project I began to take an interest in the moderate anxiety, and as I viewed most of the people I photographed as “middle men”. I am greatly interested in Bourdieu’s A Middle-Brow Art discourse. For example, a girl is in-between a child and a woman, and an Ajumma is also in-between a socially active person and a housewife. Look at me, even; I am disgruntled with my life, which is in-between. To consider myself as an artist, I am too sociological, and to be an everyday person, I lack social finesse. Perhaps because of my weak-willed nature, I’ve always lived as a “middleman”, and not a life of the golden mean. That’s been a source of my insecurity. In other words, I have not found a balance in life, but instead found myself positioned neither here nor there as a result of being indecisive. Even in my work as a photographer, I am not interested in people who are at the extreme edge of an issue or completely alienated; for example, the homeless people, or the lonely old men at Tapgol Park who evidently live tragic lives. What draws my interest are people who feel indistinct anxieties in the ambiguities of their existence. Regretfully, the military was such an organization. Their conflict between patriotism and duty, and me versus us appeared more grandiose. That is why I initially had in mind a rather vague title for my exhibit but came up with Middlemen just a few days ago.

Was there any particular reason why you wanted to photograph the army, navy, and the air force personnel all together for the Middlemen project? And what was the reason for wanting to photograph them in the course of all four seasons?

When I started working on the soldiers project, the Ministry of Defense asked me to submit an application, detailing the subject matter I had in mind. I explained that first of all I wanted to photograph the army, navy, and the air force and from there I wanted to categorize them as “soldiers and arms”, “soldiers and the body”, “soldiers and animals” and “soldiers and plants.” I simply wanted to cover all the domains of the military that ordinary people are familiar with. But it was purely for visual reasons that I wanted to shoot all four seasons. They say some film directors visualize a certain scene even before going into the actual shoot – like Martin Scorsese who pictured in his mind’s eye the blood dripping from the boxing ring ropes when he was making Raging Bull. For the Ajumma series, I thought of a woman laughing rambunctiously with her red lipstick and tattooed eyebrows; and a high school coed in her short skirt with a question mark on her face. For the soldier series, I imagined a private with a dark tanned bare torso under a tree with white blossoms against the backdrop of a blue sky. I did not manage to take that picture, but instead I photographed a pale-skinned soldier with an army dog in front of cherry blossoms against the backdrop of a blue sky. I really liked that picture. Then it dawned on me… that I also wanted to take one of a soldier in a snowy field with a bare torso, all red from the cold. I wasn’t able to do it but photographing during all four seasons was purely for visual purpose. I just happen to think visually.

I recall that you said in another interview you were working on a project that had to do with showing the facades, and not the masks of Koreans – that a mask is primarily used for covering one’s true self, and a facade is something that the person presents as his ostensible true self. So, did the soldiers “present” their facades?

Soldiers have a look that they “present.” When they stood before my camera most of the soldiers presented the look of a brave Korean soldier, which is something that they have been trained to do so without being aware of it. But that is a superficial issue and the soldiers project is not something that I worked on from the perspective of typology or facade. From the beginning, I had intended to probe into things like isolation, segregation, or perhaps trauma or compulsion.

Moderate Anxiety

You mentioned that in Korean society minute anxiety is displayed within the context of a greater anxiety, and that you are dealing with minute anxiety in your work. Do the soldiers belong to a group with similar anxieties?

That’s right. It isn’t quite like Fassbinder’s film, Fear Eats the Soul, but more like “anxiety like a mild fever.” I wanted to deal with anxiety that is analogous to catching a cold in the spring, which is minor but persistently annoying. To put it my way, it’s like a moderate anxiety rather than an extreme fear. I wanted to portray this vague and trivial anxiety of the soldiers that alienated and bothered them. What I mean by a moderate fear is the middle point between the ego and the collective. It is somewhere in between “me” and “us,” us that the Korean society incessantly imposes upon people. It seemed to me that the soldiers today have conflicting attitude about it these days. In the past, they were more simple-minded or they were more amenable to patriotism, love of one’s family, anti-communism, and the eradication of it, but whatever it was, it made it acceptable for them to endure rigid control or the injustices that they were subject to. On the other hand, they now have a more heightened awareness of human rights and more access to TV or Internet that has diminished the controlling powers. Therefore, there appears to be an emotional gap between the officers who served their military duties during the “no nonsense” era and the young soldiers of today. This is where the middlebrow fear originates. There is some kind of a conflict, but neither party can identify it and therefore they opt for a middle path. But too much of a middle path leads to absurdity. In fact, working on this soldiers project for the last two years was like seeing an absurdist play. This is what I mean, if you refer to writers like Samuel Beckett, Camus, and Sartre then it is difficult to understand. However, it can be simply stated as, “it just does not make sense.” In short, life does not always resemble a play in which there is an introduction, development, and conclusion, nor is it always in accord with common sense. The fact that I saw the military as absurdist does not mean that I view it as being immoral. It just means that I found a contradiction in a situation that isn’t quiet right as I searched for the median point between “me” and “us.”

Are you expressing this “minor anxiety” through your photographic tone? One can see your work from the 1990s, such as Americans Them, Ajumma, and Itaewon Story, which were all in dark tone, but starting with Girl’s Act it changed to mid-tone. You turned to color from the Cosmetic Girls on, as well as your current work the Middlemen. Are you showing your purpose or the concept of work through tonality?(Page 139, Cosmetic Girls)

As I am intrigued by “moderate anxiety”, “middle man” and the “middle class” my photographs naturally gravitate toward the mid-tone range. I considered the “mid-tone,” or the aesthetics of “mid-range” the prime objective of my Girl’s Act project; in particular, because black and white are too conclusive, if not decisive tones. Gray, I thought on the other hand, was more befitting of the ambiguities of the girls’ emotional vagueness. But then, the more you delve into it the mid-range tone becomes very difficult because it has incredibly dual characteristics. The mid-range tone is an emotionally very fragile and sensitive tone and it’s at the same time an objective and neutral tone. It can be used for the fragile skin tone of a young girl as well as in expressing the artificiality and the objectiveness of a landscape – like the New Topographics. The Cosmetic Girls was a color project but if I were to transform it to black and white, it would be primarily a mid-range tone work. I tried to avoid girls with extreme makeup when I was casting the subjects because given anytime, anywhere, there’ll be young girls wearing a lot of makeup – like the Karo tribe. I picked for the most part a group with “medium tone” makeup and conventional desires. The same goes for the military project. I avoided the dramatic, whether it was lighting, casting, or situations. I don’t view the military as an extremely negative entity, nor do I think of it in a positive way.

Let us talk about the backgrounds in your work. There are times when it is clearly visible and sometimes not visible. From Americans Them one can see a definite background, and Ajumma showed a rather dim one, but from Girl’s Act the background becomes very minimal, replaced by a river scene or the sky. In the Middlemen a tree, an armored truck, and an airplane are specifically shown. You said you wanted the soldiers project to reflect not only the subject but also the person in relation to his environment; now how did you go about selecting the model for your subject and the environment as the background?

In my previous works, like Ajumma, Girl’s Act, and Cosmetic Girls, the backdrop was the background, serving as a screen that doesn’t provide a story but simply an emotional ambience. But for the soldiers project, the backdrop becomes the motif, and an intentional juxtaposition. It serves as a context for an important mise-en-scène in the expression of the isolation and the segregation of soldiers. In the Middlemen project, there is a picture, with the title, “Plate no 14. The Sailor with the black glasses,” which I like. It shows an image of a sailor in a black naval uniform, standing all by himself and in the background there is a blurred military structure that looks like a broken ladder. This structure was actually dozens of meters tall, and under tight security with no close shooting allowed, but in my picture it looks like a toy. Maybe that’s my view of the military. That it’s a tragedy from up close and a farce from afar.

It seems like what the artist wants to say is very clearly expressed through the subject and the relationship between the person and the background. For example, in Ajumma if the details and the expressions of the women were very much revealed, then in the ensuing works the degree of disclosure became less.

It’s not about “revealing” but being “disclosed.” My flash photographs show a tinge of exaggeration. At any event, the Ajumma project was far more negative. But from Girl’s Act on, I tried to go more neutral although I am not sure if it actually was neutral, but at least I tried to take a neutral approach from a photographic perspective. The same goes for the soldiers project.

Does “neutral” imply that you are portraying the group in a natural way?

No, not quite. If “natural” refers to that aspect which is spontaneous, then “neutral” is something that is artificial. Don’t you think neutrality or the middle way is perhaps the most subjective? How does one determine the middle point? If one were to talk about it in reference to domestic politics these days, and the ruling and the opposition party lines were clearly defined, then it would be easy to choose “the middle,” but nowadays, there is moderate conservative, moderate left, conservative right wing people with moderate leftist politics, making it all very complicated. It also means that there is an expansion of the grey area in our society which makes it all the more difficult to pinpoint the median. For example, in the past the middle path was considered the most virtuous but you could say that because the workings of society then were much simpler. Nowadays, there’s no way to tell where exactly is the middle.

Please elaborate on the neutrality of the soldiers project.

The projects I worked on before the Middlemen were composed of people whom I could not identity with. In some ways, they were completely “them” to me. But the soldiers project was hard for me to be objective because I myself had experienced military life, and I am part of the older generation that has a definite view about the military. However, in terms of my photographic approach, I tried to be more objective, compared to my previous work.

You mentioned that depending on how your work is exhibited and how the catalog is done, the soldiers project could tell many stories.

I worked on photographing people then shifted to doing pure portraiture, then came back to taking photographs of people that, aesthetically speaking, overlapped and posed typographical and quasi-documentary thoughts and so-forth. Maybe for that reason, I could see that there were many approaches I could take after I had completed the project. Not only that, women and men had obviously differing views about my military project. I always have my work pre-screened every time I am going to have an exhibit, and I’ve never experienced such different reactions as this time. Women react to the unfamiliar weapons and military uniforms as though they are looking at some exotic scenery. What’s even more fascinating is that women are not judgmental or critical of the military. Men, on the other hand, were more punctum-minded. Most of them identified with their own military experience, and assessed it very subjectively. It’s undeniable that if you are a Korean male, then you are bound to have memories and prejudices or traumas from the military. That’s why subjective understanding is not an unexpected thing.

The Gwangju Story was done in the midst of a shooting for a Gwangju Rebellion scene, for which you had been asked to do a poster for the film, A Petal. This is the way I felt for the Gwangju Story and the same goes for the Middlemen in that at first it feels like you are seeing the actual situation but upon closer look, you start noticing some other unrealistic elements. Is there any connection?(Page 139, Gwangju Story)

When I was working on the poster for the film, A Petal, the film crew informed me that there was going to be a three-day shooting for one of the most massive rally scenes, and asked me to come to Gwangju if I were interested. That’s how I ended up photographing, like I was a documentary photographer, a crowd scene where 2,000 Gwangju citizens voluntarily took part as demonstrators. But when I saw these people sincerely acting, I began to question the truthfulness of the documentary. At the time, I was using a large-format camera called a Speed Graphic with a big flash, but people thought I was shooting with a film camera. So even when they were in the middle of a break, they would revert to acting when I started shooting, although I didn’t ask them. What dawned on me then was no matter how much of the truth I shoot, it could very well not be the truth. A film is an illusion, but shooting a scene at a location is a fact, and the actors who are being filmed are also an illusion, but again shooting them is a fact. The filmic illusion is entwined with the photographic truth. This very much intrigued me, and I began to think about the potential of documentary directing. Taking advantage of the prescribed structure and the characteristics of the documentary genre could lead to an exciting body of photographs that have been re-enacted. The soldiers project, which I am working on at present has, in part, that aspect of “quasi-documentary,” and that idea was derived from the Gwangju Story.

What are the specifically dramatized aspects of the Middlemen project?

Since I photographed the present conditions of the military basically through a format called portraiture, you can’t exclude the dramatic aspects of it. Of course, there were some that were taken spontaneously, but most of the portrait shootings were done after some observation of the subject and when the mise-en-scène was ready. It was the same for me. After the Defense Ministry gave me permission, when I arrived at a military unit I didn’t go straight into the shoot, but scrutinized the daily routine of the soldiers – like the place where they usually gathered, all their various training movements, their expressions, eye, hand, and foot gestures… Once I started taking the photographs, they would start out by simply standing straight, but after about an hour there came a moment when I caught an important gesture or expression. Sometimes a trivial behavior pattern of a soldier would come off as very significant to me; like when I asked one of the officers, who was stationed at the petty officers’ training camp, to take off his red hat; he treated it like it was a reverential object. I thought he was momentarily revealing his personal attitude toward the military, so I requested that he repeat the gesture. Like these shots that were re-enacted would indicate the intentionalist documentary feature of it, but I don’t think it diminishes the documentary nature of my work.

In conclusion, it seems to me that the title, Middlemen implies not only neutrality but also an uncertainty.

That’s right. I mentioned earlier that the military to me seemed a grand absurdist play – just like on a larger scale, the confrontational situation of North and South Korea, and on a smaller scale the generational conflict found within the military – as everything is uncertain, how could it all fit together? But it’s not like I am trying to find some logic to it through my work, and I am not even proposing that we look for one. As a photographer, I don’t think one needs to be educational or provide an answer. I simply suggest. Ernst H.J Gombrich was quoted as saying, “Artists occasionally feel that they see the quintessence of the world through their work. But it’s not the fundamental nature of the world but the heart of the artist’s response to the quintessence of the world that he sees.” I do think that this is very befitting of photographers because many of them think that they’ve seen the essence of their subjects. But it’s not the quiddity of their subjects that they are capturing, but it is instead the nature of their response to the essence of what they are looking at. Therefore, my Ajumma project does not reveal their essence, but the nature of my response to them. Likewise for the girls project and of course that includes the soldiers project. I probably did not photograph the moderate anxiety of military; instead, I am expressing the nature of my response to that anxiety that I am observing.

© 1989-2024 HEINKUHN OH