Forgetting Beings.

Oh Heinkuhn’s American Photographs

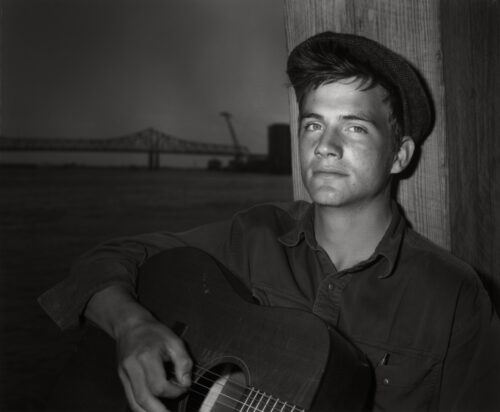

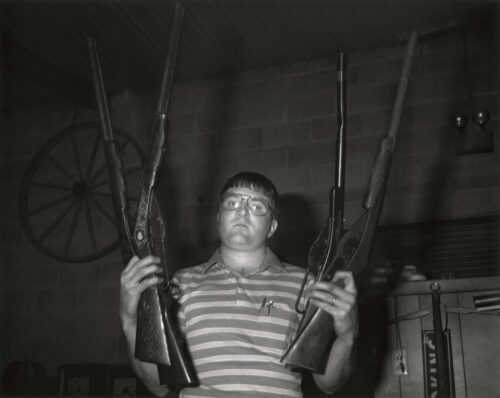

Looking at the pictures Oh Heinkuhn produced in America between 1989 and 1992, the period in which he was studying film and  photography there, we are reminded of an experience of watching a movie. Some of those appearing in this movie resemble the country singer Woody Guthrie or Frank Sinatra. We can also find the painter Salvador Dali. It is up to you the readers to find out about whom in Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures they correspond to. If you mobilize your deja-vuesque imagination, you will be able to find more actors or singers. The background is a country village of Ohio and Kentucky and New Orleans of Louisiana. What happens there can appear weird, funny, or strange to you.

photography there, we are reminded of an experience of watching a movie. Some of those appearing in this movie resemble the country singer Woody Guthrie or Frank Sinatra. We can also find the painter Salvador Dali. It is up to you the readers to find out about whom in Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures they correspond to. If you mobilize your deja-vuesque imagination, you will be able to find more actors or singers. The background is a country village of Ohio and Kentucky and New Orleans of Louisiana. What happens there can appear weird, funny, or strange to you.

But why are those people who have nothing to do with real actors and actresses look like them? What does it mean that photographs invoke scenes from a movie? Doesn’t it reveal some uncanny truth about the very fact of “seeing,” which is too common and natural to us? At this juncture, we have to think about the truth that haunts the photograph so tenaciously, the fact that it records the indexical trace of something that has once really existed before our eyes. In spite of theoretical tropes characterizing today’s images in general, such as virtual or hyper reality, the indexical nature of photography always bears some weight upon us. Let us unburden ourselves of that weight while looking at Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs.

To Korean readers who are not accustomed to American customs and culture, what happens in Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs should surely look strange. For to Koreans, America is better known through tourist stereotypical images such as skyscrapers of New York City, manors of Beverly Hills or Walt Disney World. How the common people of American countryside actually live and enjoy their lives is indeed not very well known to Korean people. However, the images of these people can also look strange to middle class Americans. If the life revolving around New York Times, Macy’s, wine or coffee at a street cafe and health food with little or no fat is thought to be normal, the life of ‘red necks’ working at farms, drinking beer rather than wine and eating fat rich fried chickens is an area of the Other. In America where lives are equalized to a great extent over diverse areas, the countryside is the Other to the urban. Just as Europeans established themselves as modern subjects while constituting non-Europeans as the Other, the urban people of America became American subject while othering the country people.

The New Deal documentary photographs of the 1930s are examples of such a successful othering. For no one thinks of those images as a realm that constitutes the country people as the Other but as “a truthful depiction of the countryside devastated by Depression and sandstorm.” However, in the sense that the readers of documentary photographs at that time mainly comprised of the people of New York or Chicago who could afford to have cultural habit and economic means to buy Life magazine and visit

art gallery exhibitions, they belong to totally different natural, cultural conditions than the subject of documentary photographs.

To Korean people, the rural people of America are doubly othered area. They were othered once when pictured in photographs, which were an urban medium (the photograph produced as a work of art and exhibited in a gallery is surely an urban phenomenon), and once more when their images were seen to Korean viewers. What matters here is the status given to people when they are turned to images. ‘Red neck’ is ‘red neck’ only when seen by urban people. By the same token, Korean people never recognize themselves as ‘yellow’ but as part of general human beings. The problem occurs when the two different systems of Korea and America meet each other. But the difference between the two systems, which is not a relative one but posited in a severe political, economical, military and cultural imbalance between two countries does not operate in Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures. In many ordinary photographs, such an imbalance vividly resides in the images of American mass culture celebrities as the ideal of beauty and charm for the rest of the world, and even working its way out into the retina of Korean people. But, as if bleach soaks out the stain out of the cloth, the American people captured in Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs are deprived of such a supremacy by the working of the camera and flashlight as well as due to the fact that they are common people living in the periphery of American society.

The flashlight exploding fiercely right in front of  the subjects’ face is never a light that shows them in an honorific way. It is a light of surveillance and observation developed by the modern disciplinary power. The flashlight exploding in front of the criminals, homeless

the subjects’ face is never a light that shows them in an honorific way. It is a light of surveillance and observation developed by the modern disciplinary power. The flashlight exploding in front of the criminals, homeless

and insane of England, France and America who wanted to conceal their identity and their

habitat forcefully took them into a bright area of administration and public health, i.e., to the realm of visibility. To be seen meant to be saved. The place reached by the administrative gaze was improved and supported. It was by being photographed by Jacob Riis that the slum of the 1920s’ New York City was saved. Child laborers working under inhuman conditions came to be protected by the law by being recorded by Lewis Hine. Indeed, Hine’s photographs decisively helped to pass the law forbidding the employment of children under a certain age for hard labor.

For the same reason, students want to be seen by their teachers, entertainers want to be noticed by producers and artists want to be watched by critics. However, the moment being seen means to be benefited by the disciplinary gaze, it also means subjection under the controlling power of that gaze. The extent to which that disciplinary power is permeated into the level of ordinary people’s lives is well revealed in American movies about fugitives trying to evade the eyes of the authority. In those movies, we can easily see scenes in which the fugitives are recognized by anonymous eyes of a restaurant or a shop employee and clandestinely reported to the police. Therefore, the fugitives do not want to be seen. They fear visibility. As there are night animals and day animals, there are types of people who are fond of brightness and who are not. And the same person can hate certain kind of light and like other kind of light. Celebrities will like the kind of light used in photography studio that glorifies them but will hate paparazzi’s flash light that exposes their private life in an less than an honorific way. It is not an exaggeration to say that what killed Diana was the flash of paparazzi. The art photography that tries to depict the object in an aesthetic manner has been attaining the artistic value by avoiding such a direct, cold light. It is a common sense of photography that diffused, soft light is used whether for artistic photography, commercial photography or portrait photography for ordinary people. It is for such a reason that the contemporary flashlight is equipped with a reflector, however small it may be, or designed to reflect light onto ceiling. Through such a mechanical and semiotic device, diffused light functions as the token for distancing photography from the light of discipline and surveillance.

However, the history of the meaning of the flashlight makes a significant turn in the works of the American photographers such as Weegee and Diane Arbus. Whereas the character of the visibility created by the flash light that depicts the subject as captured and exposed in an unprepared circumstance has been considered to be inappropriate to photography as fine art, Weegee’s and Arbus’s flash light exploding right in front of the subject purposefully resists such a meaning. It is not certain whether Weegee’s photographs of nocturnal criminal scenes of New York City could belong to the realm of fine art or not. Indeed, he rather worked as a photojournalist that used to overhear the police radio communication to follow and record spots of crime. His photographs belonged to the discourse of criminal investigation. Therefore, from the start, he did not have any motivation to take artistic photography at all. However, the visual trope of Weegee’s photographs that took away any aura that could be attached to the photographic image could certainly be posited at the other pole of the then existing artistic photography dependent upon soft, diffused light. In other words, the resistance to the artistic character of photography came from a non-artistic aspect of photography. By the same token, the people appearing in Arbus’s photographs equally look abnormal. Although Arbus created her own kind of images with the help of her interest in the psychic aspect of the people and surrealistic settings of the image, what defines Arbus’s people is the unforgiving flash light that deprives them of any chance to appropriately stage themselves in front of the camera. So, a certain person becomes an Arbus’s person. Although there is an incessant accusation that Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs resemble Arbus’s, the main characteristic of Oh’s photographs is also this burdensome light of the flash.

fine art, Weegee’s and Arbus’s flash light exploding right in front of the subject purposefully resists such a meaning. It is not certain whether Weegee’s photographs of nocturnal criminal scenes of New York City could belong to the realm of fine art or not. Indeed, he rather worked as a photojournalist that used to overhear the police radio communication to follow and record spots of crime. His photographs belonged to the discourse of criminal investigation. Therefore, from the start, he did not have any motivation to take artistic photography at all. However, the visual trope of Weegee’s photographs that took away any aura that could be attached to the photographic image could certainly be posited at the other pole of the then existing artistic photography dependent upon soft, diffused light. In other words, the resistance to the artistic character of photography came from a non-artistic aspect of photography. By the same token, the people appearing in Arbus’s photographs equally look abnormal. Although Arbus created her own kind of images with the help of her interest in the psychic aspect of the people and surrealistic settings of the image, what defines Arbus’s people is the unforgiving flash light that deprives them of any chance to appropriately stage themselves in front of the camera. So, a certain person becomes an Arbus’s person. Although there is an incessant accusation that Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs resemble Arbus’s, the main characteristic of Oh’s photographs is also this burdensome light of the flash.

However, instead of exposing people in an unforgiving manner, Oh Heinkuhn’s flashlight works to put them in a different context. That is the point at which Oh Heinkuhn can be relieved from the burden of Arbus. That relief comes from Oh’s habit of purposefully forgetting the distinction between the real and the fiction. In several cases, he produced pictures in which this distinction was unclear.

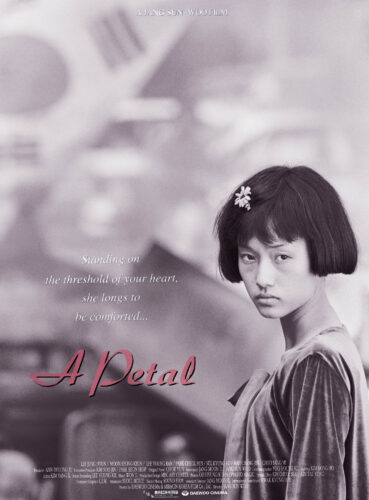

For instance, when he worked for the poster of the movie, <Petal>, which was about the Kwangju People’s Uprising, he took picture of a lot of spectators watching the movie making scenes in the street along with actors who were acting as demonstrators, soldiers or spectators of demonstration. Even though those actors were real, they were not real demonstrators or soldiers. However, their ‘acting’ as demonstrators and soldiers was a real

situation. Even more, it was impossible to tell some of the spectators from the actors. To purposefully forget the distinction between the fiction and the real means that the method for such a distinction is purposefully not employed. In other words, the method of documentary photography was used but the images did not look documentary.

In the pictures Oh Heinkuhn produced in America, there are many instances in which it is impossible to tell whether the subject is a real person from rural America or an actor.

Even in the case in which he or she is a real rural person, it is uncertain whether he or she is willingly acting in such a manner or just taken picture by chance. For example, some people are agape with astonishment as if encountering a UFO. But it is uncertain whether they are really seeing a UFO or just surprised by something else.

Such an uncertainty is emphasized more by a totally unorganized gaze working in Oh’s photographs. The subjects of his photographs stage their expression as if the camera were never in front of them and their gaze is free from the camera lens. The gaze of the lens is not directed toward the subject, but to other things in the background. Such a gaze was not intentionally endowed by the photographer. Since the viewfinder of the Graflex camera Oh Heinkuhn used for these pictures partially hid the periphery of the picture frame, the camera played a trick of putting anything it wanted within the frame of the photograph against the photographer’s will. That means, the photographer does not have the total control of what is captured by the lens. Therefore the camera’s gaze exceeded the photographer’s intention. Such an excess, however, resulted in producing interesting spectacles to the viewers. They are the things like a cut-off signboard that is illegible and strangers who accidentally appear inside the picture frame. In most of the cases, their look is directed to something else and they don’t seem to feel guilty of ruining the ‘proper’ composition of the photograph. But in Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures those ruined images offer us visual pleasure.

Perhaps many of us have experience of attempting to paint a picture but ending up in ruining it due to a mistake or a lack of skill in our elementary school days. Even when such a ruining is neither a result of fundamental misconception of the rules of painting nor vandalism against the masterpieces but of a slight mistake or accident which could be revised later, children used to despair and tore apart the paper. Oh Heinkuhn had the same attitude toward his own photographs. He once considered many of these pictures ‘ruined’ due to the unexpected interruption of a stranger into the frame or awkward composition resulting from the limited visibility of the viewfinder and discarded films of those pictures. The strange stain-like strips in some of the pictures in this book are wounds from the ones saved after having been discarded. Not only in the pictures physically ruined, but also in the well preserved pictures, we can witness a lot of excesses of meaning since the photographer himself does not have a total control over them. Such a meaning resides in the form of narrative in each of the images.

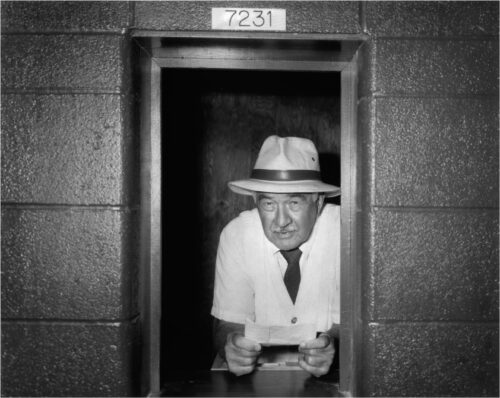

For instance, a military police woman wearing a name tag, “Conor,” who has been caught by the camera while looking at something outside the picture frame with a rather sad, frail face looks like a character appearing in the midst of a movie. Her short and strong sounding name gives an impression that she must have been a movie character. Just like other American military personnel she is well disciplined. However, while attending to her duty, she comes to notice a past lover in the midst of the distant crowd. While being unable to forget her memory of love, she has to go back to her position as an official person with a broken heart. For this memory, she can not control herself and becomes an alcoholic. A man wearing mustache a polka-dotted cap and nylon pants with suspenders looks like a farmer but is certainly a main character of a gangster movie.(p. ) His face conceals the sly, arrogant and clever feature of a cheating man who takes his mother- in-law’s possession in a cunning manner. Though the Fargo’s main character, Jerry Lundgrun, was a silly cheating man who got caught by the police and lost his wife and

“Conor,” who has been caught by the camera while looking at something outside the picture frame with a rather sad, frail face looks like a character appearing in the midst of a movie. Her short and strong sounding name gives an impression that she must have been a movie character. Just like other American military personnel she is well disciplined. However, while attending to her duty, she comes to notice a past lover in the midst of the distant crowd. While being unable to forget her memory of love, she has to go back to her position as an official person with a broken heart. For this memory, she can not control herself and becomes an alcoholic. A man wearing mustache a polka-dotted cap and nylon pants with suspenders looks like a farmer but is certainly a main character of a gangster movie.(p. ) His face conceals the sly, arrogant and clever feature of a cheating man who takes his mother- in-law’s possession in a cunning manner. Though the Fargo’s main character, Jerry Lundgrun, was a silly cheating man who got caught by the police and lost his wife and

father-in-law while attempting to take his money, this man in Oh Heinkuhn’s photograph is different. He is acting a well-shaped cheating man.

A middle-aged man looking from behind a ticket office is saying, “The last train to Davenport has already departed. Come tomorrow. Unfortunately, there are not many fun spots to spend the night in this town. Your only choice will be to sip tequila at Tamy’s Bar at the corner of the Main Street.” Our hero leaves the station with a lonely posture and disappears into a rainy night street. Quite strangely, anybody who buys a ticket at this office seems to be doomed to miss the train. Two country farmers with stubborn face say, “they will never show up at our town again. If they come again, I will kick their asses with this Winchester.

You will learn to respect Coldwell.” (p. ) They might be the very farmers who shot Jack Nicholson and Denis Hopper riding motorbikes without any reason at the last scene of Easy Rider.

The astonishment of a middle-aged couple is really fictional.  Their eyes are wide as if witnessing some tremendous spectacle. “Honey, look. At last, the Martian people in front of us. What should we do? What are those long antennae-like organs?” The husband replies. “Don’t be too afraid. They may be our friends. The aliens found in Roswell in 1953 were friendly.” Or they might just be watching a fireworks

Their eyes are wide as if witnessing some tremendous spectacle. “Honey, look. At last, the Martian people in front of us. What should we do? What are those long antennae-like organs?” The husband replies. “Don’t be too afraid. They may be our friends. The aliens found in Roswell in 1953 were friendly.” Or they might just be watching a fireworks

There is a voyeuristic curiosity in this type of watching into American lives. It was perhaps possible because Oh Heinkuhn was an alien rather than a ‘normal’ American in the midst of the American style of life. While working on these photographs, Oh Heinkuhn was a student of film and photography with no ties to the American culture, institution and custom other than through a scant position as a student. Therefore, he had no room to locate himself inside the American life and culture. A student is basically a little bit unstable position open to all the possibilities but for whom nothing has yet been realized. In the sense that Oh Heinkuhn was a Korean student temporarily visiting America for study, he is doubly an alien to the reality taken picture here. For such an alien, the Graflex camera’s wide body using 4×5 inch film must have been a good cover to hide himself. That might be the reason why no one in his photographs looks like a main character.

However, as is usually spoken in Korea, it is not because they are originally alienated people that they don’t look like main characters. They are never alienated. A cross- dressed gay man sitting on the ground in Mardi Gras with an exhausted look is never alienated. An old couple hugging each other with rather sad faces in a country bar is never alienated. Rather the alienation is a bad habit of projecting the sentiment of the intellectuals, artists and students who have failed to establish certain positions within the confused cultural mapping of 1990’s Korea. Whether in Korea or in America, living people are too busy to be alienated. They are busy accepting the conditions for producing the subject imposed upon the social grid systems and act as the subject within them. If the people in Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures look lonely, that is only a sentiment projected onto the picture. Projection is a bad cultural habit. The reason why the people in Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures don’t look like main characters is entirely because of Oh’s own method of taking picture. At home, they act as main characters in their own family pictures in their own manner of visual representation. They have been got rid of their status as main characters because they were captured by Oh’s camera regardless of their will. This status in which a person is located at the physical center of the picture yet not as a semiologically main character is a decisive point that tells why Oh Heinkuhn’s pictures are intriguing.

The outstanding feature of Oh’s photography lies in the fact that he takes picture without confronting the subjects head to head and captures them  at the moment when they are not ready to pose for the camera. As a result, the subject of the photograph is evicted of

at the moment when they are not ready to pose for the camera. As a result, the subject of the photograph is evicted of

his or her position as the main character. In addition to it, borrowing the voyeuristic vision of the camera, Oh Heinkuhn looks at rituals of American lives such as country auctions and Mardi Gras Festival with a curious eye. Although those rituals might be familiar rituals for Americans but they can look strange and alien to Korean viewers.

Korean people think that they know America well, but the point described above constitutes the crooked vision on the part of Korean people and this vision then turns to cultural differences. The crooked vision here means the way of seeing that renders what is familiar unfamiliar. Just as the shape of a thing is transformed when we look at it with a crooked vision, the fact that Oh Heinkuhn and Korean viewers of his pictures live in different culture from that of America renders its everyday life in a different shape. Of course, the crooked vision also intervenes when American viewers look at the images of everyday life of Korea.

Such a crooked vision is neither a vision of observation nor that of surveillance. It seems that with such a crooked vision, Oh Heinkuhn forgets the people rather than ‘looking at’ them. He is forgetting who they were, whether they are real people or movie actors, just as the cameraman for a movie is forgetting whether he is taking picture of real person or a character of the movie. Oh Heinkuhn’s habit of forgetting to differentiate the fiction from the real has reached the point in which he has forgotten where his real hometown is. (I don’t know where he was born. He told me that he was born and grew up at Itaewon, one of the tourist districts of Seoul, but I know that is a lie. For people are not born in Itaewon. I didn’t tell him about my hometown either. For I was also afraid he would not believe where I was born.) So he tries to find his hometown in Ohio and locate the hometown people from the faces of strange American people’s. Although photographs are a means to replace memory, they are also a means to forcefully erase memory. Or, rather than a means, they are a site of forgetting. We are forgetting something ‘in’ his photographs rather than ‘through’ them.

In these photographs it is forgotten who those people were, what their names, occupations and personal characters were. Therefore they have no inside. Something we call inside, which is neatly organized and waits to be expressed through language, behavior or art to the outside is just lacking in them. They only have their roles to play. They appear to have their inside only because their act coincides with the frequency of the Korean viewers’ deja-vu. Therefore their act is ‘real’ just as the image resulting from the act of an actor is not real; his act itself is real.

Thus, for the first time, through Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs, we can see people in their undisguised, pure state. In spite of the sly yet stupid connotation of the word, ‘undisguised,’ Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs really show people in their undisguised condition. For he took picture of the people before they are ready for it. Susan Sontag once dubbed this capability of the camera that takes its object by surprise ‘soft murder,’

but such a manner of revelation is the very aspect of photography which surpasses other media of arts such as painting, drawing, video or computer graphics which are considered to be either historically or technologically superior to photography. If we can not confront the object head to head, where can we confirm the existence of this world? If we always have to wrap the object with aesthetics, sensations and sentiments for fear of confronting it in its raw state, nothing in this world will be felt as alive, including ourselves confronting it. The reason why Roland Barthes disdained fine art photography was because what is seen in it is the skill and code of wrapping up the object rather than the courage and trauma experienced when confronting it. We can see things through Oh Heinkuhn’s photographs. That is why people feel uneasy about his photographs. They are uncomfortable to ‘them.’

Written and translated by Young June Lee <image critic>

© 1989-2024 HEINKUHN OH