DEADPAN Photography, History, Politics

Hein-uhn Oh’s works references the May 18 Democratic Uprising of 1980 in Gwangju, South Korea, a civil protest during which at least 165 people were killed. Seven ink-jet prints from Oh’s 1995 series Kwangju Story document the recreation of the film about it. The disconcerting ambivalence of this images forces the viewer to confront their own reponses to these crucial events in the recent history of South Korea…

-Geoffrey Batchen, Jeehey Kim, Jung Joon Lee

Creating Awareness, Challenging Thought

What are we supposed to make of the photography by Hein-uhn Oh? Two men and some children stand around looking bored, even by the act being photographed. They’re shot from below, so we can’t see what else they can see. In any case, they’re looking in a number of different directions, as if there is nothing in particular to catch their attention. Seen from below and with the sky behind them, they have a monumental presence, like statues. Elsewhere, four young men stand top of something, yelling and gesticulating while one of them waves a huge Korean flag.

They’re again shot from below, throwing them into relief against the sky. The action seems dramatic, heroic, designed to become iconic(almost as if they are copying the gesture from a photograph). One group is spectators, and the other comprises a bunch of actors, but they are both engaged in an act of collective recall. For these Photographs document the 1995 filming of a recreation of the Democratic Uprising of May 1980 in Gwangju, a provincial city in South Korea. Over 165 people were killed by government troops during this ten-day uprising, a traumatic memory for many Koreans, and a crucial turning point in the struggle to end a U.S.-backed dictatorship and institute a democratic form of government.

Oh’s photographs remember these events or is it that they remember only their recreation fifteen years later? What the difference? The original events have already been displaced by a movie version that was itself partly based on news photographs from 1980, and now Oh’s Photographs displace that displacement, substituting a few fragmentary scenes for the movie’s narrative coherence. Posing as journalism, slipping uneasily between fact and fiction, and refusing the usual self-ongratulatory myth-making that accompanies official commemorations, Oh’s series casts a baleful eye on the past, or at least on the relationship of past and present articulated by this thing we call ‘history’. He also casts a skeptical eye on documentary photography and its presumed capacity to tell us the truth of a given situation. For these photographs refuse to dig deep below the surface of appearance. Nor do they embellish their subjects with empathy and thereby a resolution of our own uncertainty in front of them. A young man in a soldier’s uniform glances back at us, his face neither welcoming nor hostile. His blankness demands we do all the work. What meanings should be ascribed to him, a schoolboy pretending to be a soldier for the sake of a camera? What meanings should be ascribed, for that matter, to the uprising in Gwangju, the story this boy is meant to be representing? You had better decide, because these photographs sure won’t do it for you.

-DEADPAN’ , Geoffrey batchen, pp6-7 May 16, 2008

Deadpan Rhetoric: we don’t have an alibi

Deadpan photography is unkind, making the beholder uncomfortable by failing to satisfy her desire for transparency. Hein-uhn Oh and Walid Raad demythologize the binary of truth and fiction, which derives from the false assumption that fact is equivalent to truth, and fiction equivalent to falsehood.

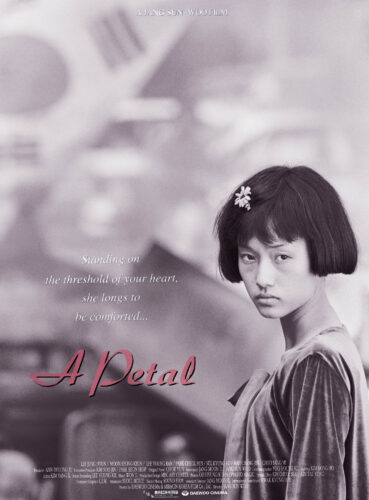

Oh also explores the way photography can go through the border between the real and th e imaginary. Feature films and other media construct narratives previously familiar to the au dience, often aestheticizing and making the past and unfortunate events involving the Other bearable and plausible. Oh, through his use of deadpan rhetoric, achieves something else. His photographs convey the fact of fiction, recording the making of a film called A Petal, which Jang Sun Woo, the director, produced in reminiscence of the May 18 Democratic Up rising of 1980in Gwangju. Oh not only photographs actors being filmed but also ordinary ci tizens, including policeman, at the moment of filming. Thus, his photographic images are fr amed neither within the film nor outside of the film. In addition, they are posited in an am bivalent temporal/spatial border between the Gwangju of 1980, both as the time/space of t he real event and as fabricated for filming, and the Gwangju of 1980, both as the time/sp ace of the filming, which normally would be concealed within the film, and as the real spa ce for Gwangju’s citizens, Thus, the viewer beholds Gwangju in 1980 and 1995, as well as Gwangju’s citizens from both years.

I find this play of diegesis and non-diegesis integral to what Homi Bhabha calls mimicry:

What emerges between mimesis and mimicry is a writing, a mode of representation that m arginalizes the monumentality of history, quite simply mocks its power to be a model, that power which supposedly makes it imitable. Mimicry repeats rather than re-presents.

Oh’s works function as “parodists of history,” refusing “to be representative, in a narrativet hat refuses to be representational.” Here, “the desire to emerge as ‘authentic’ through mim icry – through a process of writing and repetition – is the final irony of partial representatio n.” Considering that all af Oh’s photographs are gated September, 1995, I see his works f unctioning as a menace to authority. No less than 616 citizens submitted a written accusat ion to the Korean government on May 13, 1994, naming thirty five people responsible for t he violent suppression of May 1980. Surprisingly, the Prosecutory Authorities announced th at there was no right of arraignment as of July 18, 1995, starting that the case was inappr opriate as an object of judicial review since the event occurred during a political process t o establish a new constitutional system. A series of resistances and complaints (through le tter and official petitions) followed, including the issuing of a statement by college profess ors, and this provoked the establishment of a special law to cover the May Democratic Upr ising, under which there is no statute of limitation on crimes associated with the event. Thi

s new law was announced on December 21, 1995. A petal was released the next year. Oh ’s photographs show us 1995 Gwangju citizens, who have never forgotten about May of 1 980, and were even then waiting for an historical judgment of their Uprising: for these citiz ens “mimicry conceals no presence of identity behind its mask. The deadpan-

ness of these citizens and actors beard the acuity of the gaze of the Other.

– DEADPAN’ , Jeehey Kim, pp10-11 May 16, 2008

On Immediacy and Responsibility

There are times, however, when photographs have the power to become agents of change . When the photographs of the dying student activist Han Yeol Lee was published in daily newspapers in the midst of the Korean democratization movement in June 1987m the Kore an public rose up against the oppressive military government. The image shows two young college students in front of a demonstration. A masked student holds Lee, who has collaps ed after being hit by a teargas bomb. The image of blood dripping from his head ignited

a massive wave of organized civil demonstrations. Criticism from the international communit y of the Korean government at a time when preparations were being made to host the su mmer Olympic games also pressured the regime to concede to public demands. The result was that the people of Korean secured the right to vote in presidential elections.

Twenty years have passed since the death of Lee was captured in the photograph that hel ped bring ‘victory’ to the people. The complexity of the politics of the democratic moveme nt still informs the current political climate in Korea. That history lives on, but what about t he life of the photograph? What kind of role would it play today in telling the history of th e Korean democratic movement of the 1980’s The image has been popularly reproduced a s embroidery on flags, as woodblock prints, and as silk screens to be hung in museums, and it regularly reappears in commemorative event. It seems that the blood of Lee no long er causes people to react as they did twenty years age.

If the image carries a different meaning today. it necessitates that we read and tell history differently.Heinkuhn Oh’s photographic series, Kwangju Story, is one of numerous visual pr ojects that deal with the May 18 Democratic Uprising of 1980. Oh’s photographs have a d eceptive element. The image of a group of people standing on top of a structure waving t he Korean flag is reminiscent of many widely circulated photographs of the Korean democr atization movement of the 80’s. Is this scene real or fake? Kwangju Story creates a sense of eeriness that is not expected in the depiction of a violent clash between government tro ops and student demonstrators. In the photograph two children stand with their father by t he scene of that event; in another, local policemen stand quietly with their arms folded. C ould they really be scenes from what is known to be the most violent clash since the Kora n War? Oh recorded these puzzling scenes as he photographed the filming of the reenacte d May Democratic Uprising for the movie, Kotyip(A Petal), produced in 1995. The scenes were filmed in downtown Gwangju, the main area where civilians in that city were massacr ed on May 19, 1980. Some of the extras featured in the film were actual participants in th e Democratic Uprising. Young residents of Gwangju played both the students who were kill ed and the soldiers who were ordered to kill them.

Oh states that “what attracted [him] to photograph the scenes was this absurdity that the crowd created in the process of transforming the unbearable truth of the Gwangju Democr atic Movement into a digestible fiction.” His final remark about the project throws the word

‘truth’ at us once again: “If felt a true feeling here, wouldn’t that be ‘the Photographic Tr

uth’? However, his use of the word ‘truth’ here is deliberately ambiguous. He identifies wh at he truly felt while making the photographs with what he is convinced is the Photographi c Truth. What the photographs show him is not truth of the subject but the truthfulness of his feeling about the history of the May Democratic Uprising.

Oh’s Kwangju Story bypasses the imaginary burden of documentary photography to compel us to act. It is, after all, a fictional representation. Free from the burden of being docume ntary, these photographs engage us on a different level. They no longer have a ‘shock’ val

ue, but rather draw our attention to the aftermath since the May 18 Democratic Uprising. T hose responsible for the massacre have continued to proper; rumor has it that one of the m even owns property on 32nd street, not far from the Graduate Center. How, then, would

Gwangju residents react to Oh’s fiction of the past? How should we? Are not democracy and equality still contentious issues in Korea? How about here in the U.S., for that matter?

An image cannot give us a definitive answer to these questions. The impact of Kwangju S tory, however, is the very fact that the images ask us to confront such questions.

To a Korean audience, the fine line between fact and fiction in Oh’s Kwangju Story is a c onstant reminder of the country’s past, its present issues, and its possible future. For this audience, the immediacy of history conveyed by those images is almost inevitable. One ha s to wonder if they can have same impact on people who are less affected by the history

of the Korean democratic movement. All of these issues present us (all of us, not just Ko rean) with the following dilemma: how should we represent ‘our’ history to those who see i t as that of Other? In turn, how should we approach a history of Other through images?

-‘DEADPAN’ , Jung Joon Lee, pp13-14 May 16, 2008

© 1989-2024 HEINKUHN OH